What is intersectionality?

For Black History Month, Georgina Phillips, School Recruitment and Relationships Officer for Gender Action, has written a introduction to the concept of intersectionality.

Feminist issues and debates have become increasingly prominent in the news cycle today, with discussions of the #MeToo movement, reproductive rights, ‘toxic’ masculinity, equal pay and the gender pay gap, regularly making headline news.

With this growing awareness in feminism and feminist theory, there has been increasing interest in the term ‘intersectionality’ especially over the last four years, as you can see from the Google Trends graph below.

In her book ‘Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism’, bell hooks points out that people frequently discuss ‘women’s rights’ and ‘black rights’ as if they were separate issues, seemingly forgetting that some women are black, and some black people are women.

This means that black women and their concerns often get marginalised; their issues as black women are often side-lined in women’s movements that are dominated by white women, and their issues as black women get side-lined in civil rights and anti-racist movements. This means that black women are often being told to minimise their ‘blackness’ to focus on women’s rights, or diminish their concerns about feminism to support the civil rights movement. This altogether negates the realities that these women experience both as black people and as women, and particularly ignores the specific oppression they encounter as black women.

It was this culmination of different types of oppression, and the specific experiences that occur when identities intersect, that led Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw to coin the term ‘intersectionality’ in 1989. You can watch this video here to see the Professor herself explain what brought her to coining the term.

As intersectional analysis has developed, it has moved to look beyond how race and gender intersect, to also look at how other types of identity, such as:

Class

Sexuality

Gender identity

Religious beliefs

Disability

and socioeconomic background

…can interact with each other to affect how an individual may be treated in different situations, such as those below.

RELIGION x GENDER

Muslim women who wear the hijab can receive a disproportionate amount of Islamophobia as they are more visually identifiable.

Assumptions about their oppression within their community are also made by non-Muslims.

Watch more about this issue here.

RACE x SOCIO-ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

Being wealthy often allows you to avoid certain forms of oppression, but people of colour are not immune to racism just by being in a higher class.

Wealthy people of colour are often held to higher standards than their white equivalents.

NEURODIVERSITY x GENDER

Autism is often thought of as a ‘male condition’ which means women are often less likely to be diagnosed, and therefore supported.

Read more about this issue here.

“...there is no single “Black” identity that is not also gendered and classed—and no form of “femininity” that is not also at once racialized and classed in some way, and so on.”

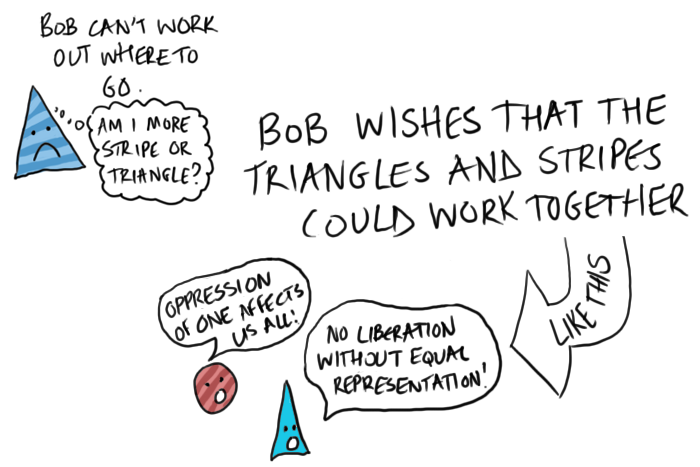

This labelling, naming and exploration of issues is often dismissed as ‘identity politics’, as something divisive, when in reality, gaining an intersectional perspective shows that we are complex individuals that cannot be just reduced to just categories like ‘queer’, ‘white’ or ‘working class’. If anything, an intersectional approach disrupts the traditional blocs that people are often allocated to.

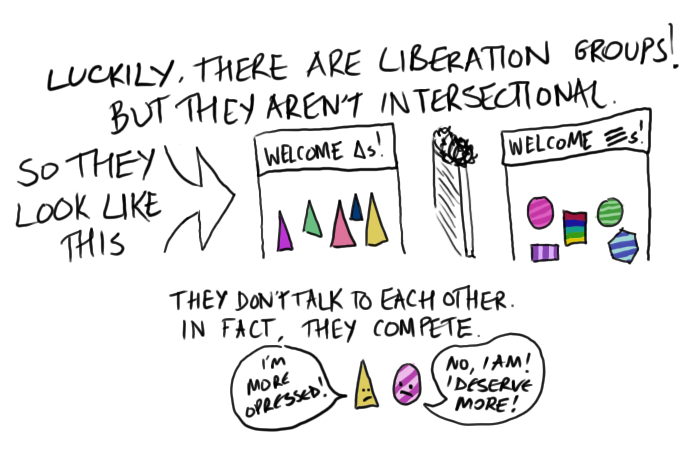

Breaking down people’s identities into smaller and smaller categories is also critiqued for generating an ‘oppression Olympics’ of who is the ‘least privileged’ or who ‘has it the worst’. In fact, considering identity in an intersectional way, builds an appreciation that at different times and in different contexts, people can experience different levels of privilege and oppression.

“Ultimately, men are men…However, the goal posts shift based on race, class, sexuality and so forth. When it is ‘men’ who are being referred to as a…group, it is important to also look at the distinctions between men”

Considering intersectionality is important when looking to do work in education. Assumptions are often made about groups, and having an intersectional approach helps you consider that a project may not benefit everyone in a group equally. Projects for ‘girls’ or ‘boys’ may not consider issues around race, religion, sexuality, gender identity, or class, which may have a big impact on the efficacy of your programme. Work is also often orientated around what may benefit more privileged members within a group – this is why ‘mainstream’ feminism is often critiqued as ‘white feminism’ because aims, practices and priorities of these groups are focused on the aims and priorities of white women.

We really enjoy this fun guide to intersectionality by Miriam Dobson, which shows not only how oppressions can overlap but also how resources are often focused on helping specific types of identity. This shows why initiatives can be ineffective if they do not consider that an individual may be dealing with multiple oppressions. When multiple oppressions like racism, colourism, and sexism, combine and act together, they can become complex and require more than tokenistic or simple solutions, to approaches that are sensitive to difference.

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

Although Gender Action has not required intersectional goals, many of our schools have taken an intersectional approach to their work in challenging gender stereotypes:

“This project aims to challenge the curriculum to be as diverse as the students it is designed for. The goal will be to see a curriculum in which gender roles are challenged and in which children from all backgrounds, especially those from black and minority ethnic backgrounds (BAME), see themselves represented in the characters and historical figures studied over the course of their academic journey at our school.”

“Ensure practices throughout the school allow students identifying as LGBQT, as well as parents identifying LGBQT, to feel welcomed, experience success, and see their experiences represented throughout our school and our larger community.”

“The goal is to address and challenge existing gender stereotypes in relation to the perceived employment possibilities and career goals held by the school community (staff, parents and pupils). This work builds on the work the school has already done with Black Caribbean students and is also being driven by the increasing amount of pupils questioning their gender identity and the school now strives to best place itself to support all pupils with navigating gender issues in all forms.”

Many schools also acknowledged that they have diverse classrooms and cohorts and that this would be considered in their work, rather than treating ‘boys’ and ‘girls’ as two distinct, homogenous groups.

“When feminism does not explicitly oppose racism, and when antiracism does not incorporate opposition to patriarchy, race and gender politics often end up being antagonistic to each other and both interests lose.”